There’s a difficulty in cataloging discreet instances in the Song of Song where the imagery of flowers in invoked. The Song, crucially, is a song set in spring, and the scent of what we might call a “floral logic” (budding—ripening—blossoming) is favored by the Song in a diffuse manner. The flowers of spring are mentioned early in the Song to indicate that winter has gone, and “the time of pruning has come” (2:12). Everything is in love, and everything is in bloom (cf. Zohar 1:43b).

Thus “flowering” and “blossoming” are motifs as essential to the Song’s symbolic structure as flowers themselves. The Song employs strange words to speak of this activity; סְמָדַר (semadar), used to describe the blossoming of grapevines in 2:13–15 and 7:12, is found nowhere else scripture.¹ The male lover is known to have a number of orchards and gardens on his property and is keen to describe the fruitful “blossoming” (הֵנֵ֖צוּ, henetzu) and “flowering” (פָּרְחָה, parecha) of his pomegranates and grapevines respectively, a common agricultural motif which takes on floral language to suggest an interest in generation and fertility basic to the Song. Thus by tracing the use and interpretation of certain distinct floral images in the Song we can hope to better understand the mysteries of the Song in their essence. Furthermore, reading the reception of the Song’s flowers offers us a unique case study in the manner with which scriptural exegesis effectively shaped humanity’s understanding of the natural world in the Western middle ages.

On the “shoshanah”

Two flowers with relatively precise definitions are mentioned once each in the Song: the crocus (2:1a) and the mandrake flower (7:14). More mysterious is the image of the שׁוֹשַׁנָה (shoshanah). This is the most frequently invoked flower in the Song, and one of its most celebrated poetic images. The shoshanah is mentioned seven times²:

- 2:1, “I am a rose [chavatzelet] of Sharon, a shoshanat of the valleys.”

- 2:2, “Like a shoshanah among thorns, so is my darling among the maidens.”

- 2:16, “My beloved is mine and I am his, who browses among the shoshanim.”

- 4:5, “Your breasts are like two fawns, twins of a gazelle, browsing among the shoshanim.”

- 5:13, “His cheeks are like beds of spices, banks of perfume. His lips are like shoshanim; they drip flowing myrrh.”

- 6:2, “My beloved has gone down to his garden, to the bed of spices, to browse in the garden and to pick shoshanim.”

- 7:3, “Your navel is like a round goblet—let mixed wine not be lacking! Your belly like a heap of wheat hedged about with shoshanim.”

As a way into determining the identity of the shoshanah I’ll say a few things about the word’s etymology. The Hebrew root š-š-n is thought to be borrowed from the Egyptian zšn / zeshen (hieroglyphic M9 in Gardiner: 𓆸), meaning “lotus.” From zeshen is also derived the Greek σοῦσον (sousson, whence the name “Susan”) and the Arabic سَوْسَن (sawsan), both of which apparently mean “lily.” Herodotus clarifies the matter, writing ca. 430 BC that “what is known in the Greek world as a lily is called a lotus in Egypt.”³ This is probably why the Septuagint chose to render the word as krinon (“lily”), although why this was preferred to sousson is unclear to me. The Vulgate opts less ambiguously for lilium, anticipating the taxonomical identification of the Song’s flower as the lilium candidum or “madonna lily”—a flower native to geography of the poem.⁴

There’s little doubt, to my mind, that “lily” is an appropriate translation of shoshanah. I’m less eager in my biblical-botanical speculation to settle on the lilium candidum than some, however, especially if it’s to the exclusion of the nymphaeaceae (water lily) family. While this latter species is foreign to Jerusalem it was a common motif in Egyptian love lyrics and was likely known to the poets of the Song.⁵

Furthermore, as Munro notes, the choice between lilium candidum and nymphaea has implications on how we imagine the Song’s geography: if the female beloved is compared to a water lily then the valley in which the Song is set is a river valley, and the fawns who “browse among” these flowers (2:16) are in fact drinking at the riverbank. This is concordant with other instances in the Song where the woman is associated with water, such as in her comparison to a “sealed-up fountain” and a “garden spring” (4:12–15).⁶ Aquatic symbolism in reference to women resonates with the succeeding Hebraic tradition—think of the “feminine waters” of classical Kabbalah (e.g., Zohar 1:18).

Rose, lily, or crocus?

It’s not obvious to me when shoshanah began to be translated as “rose,” especially among Jews. To cite an early example, Shir haShirim Rabbah relates a legend concerning a rose in its explanation of Song 2:2. Likewise, the Metsudah rendering of Rashi’s commentary has his comments to Song 2:1b refer to the “rose of the valleys”—a variety which the exegete keenly notes to be more beautiful than the flowers of the mountains by virtue of the geography’s moisture (continuing our theme of water symbolism).

Even more strikingly, Rashi clarifies the first section of this verse (“I am a meadow-saffron/rose/crocus [חֲבַצֶּלֶת, chavatzelet] of Sharon”) by noting that the flower in question here is identical with the shoshanah. He writes: “Of chavatzelet—this is [literally “she is”] a shoshanah.” The Sefer Duda’im (“book of the mandrakes”) attempts to resolve the question by explaining that a young rose is called a chavatzelet while a mature one is known as a shoshanah, the latter being particularly well suited to valley climates. Thus we find that the two flowers of 2:1, neither of which likely refer to roses in the original sense, are read here by the medievals as two different words for “rose.” Fascinatingly, the word is used in Modern Hebrew today exclusively to refer to roses—the influence of a medieval tradition.

In fairness, Jastrow points out that the chavatzelet likely finds its etymology in the root chavah or chavi (חֲבָא, חבי) meaning “to cover.” This would indicate that the chavatzelet refers to a young flower whose leaves have yet to fully unfold and disclose themselves; per Jastrow: “as long as the lily is small, it is named chavatzelet, when it is full-grown it is named shoshanah.” The suggestion here seems to be that the two flowers have been thought traditionally to belong to the same species, regardless of what that species is (Jastrow seems to air on the side of lilies over roses). The equation of these two species resonates well with the structure of this verse but does little to provide precedent for the medieval reading of the shoshanah—or the chavatzelet, for that matter—as a rose.

A mandrake interlude

Following rabbinic tradition (e.g. TB Eruvin 21b:2), Rashi likewise (mis)reads the “mandrakes” (דּוּדָאִים, dudaim) of Song 7:14 as “baskets” (דּוּדָאֵי, dudaey) of figs; thus, per his revision of the verse: “the baskets emit fragrance.” The allegorical interpretation of this reading posits the baskets of good and bag figs as representative of the righteous and sinful among Israel respectively. Despite the difference in quality and spiritual prowess, all of these baskets of figs emit a fragrance—likewise, “all of them [the people Israel] seek Your countenance.”

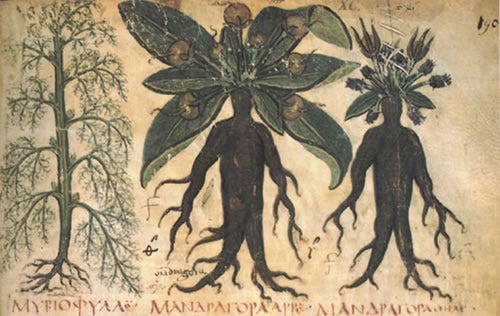

The association of mandrakes with human free will finds an uncanny parallel with the Physica of Rashi’s near-contemporary Hildegard von Bingen. Hildegard here writes that the mandrake (or mandragora) “grew from the same earth which formed Adam, and resembles the human a bit”—a fact that medieval illustrators would like to exaggerate, as shown below. Hildegard continues:

Because of [the mandrake’s] similarity to the human, the influence of the devil appears in it and stays with it, more than with other plants. Thus a person’s good or bad desires are accompanied by means of it, just as happened formerly with idols.⁷

Because of the human form of its root Hildegard understands the mandrake plant (like Rashi’s fig baskets) to be a symbolic repository for the extremes of human will and potential. The Adamic quality of the root seems to put it at risk of occult exploitation. Hildegard is quick to recommend that the reader place the entire plant in a spring for a day and a night so that the accompanying spirits might be expunged from it and that it will have “no more power for magic or phantasms.”

Those familiar with Hebrew will also note the similarity between dudaim and the word used for “love” and“beloved” in the Song: dodi, dodim (from דֹּד). No cognate, in Hebrew, is ever a coincidence. We thus see in the story of Jacob, Leah, and Rachel’s courting (Genesis 30:14–16) the role of mandrakes (מִדּוּדָאֵ֖י, medudaeh) as a symbol of romantic love. From antiquity well into the middle ages the plant was associated with eros (owing in part to its human shape) and was well known to to be an aphrodisiac, a medical tradition which has informed certain Hasidic reading of Jacob’s transaction. While the plant’s credibility in medieval medical writing can be attributed to the account in Genesis, its verse associations with eros (as attested to especially in German love poetry) should also be ascribed to certain liturgical uses of its mention in the Song of Songs.⁸

“Shoshanah” as rose in classical Kabbalah

In his notes to the first line of Sefer ha-Zohar (“Rabbi Hizkiyah opened, ‘Like a rose [shoshanah] among thorns so is my beloved among the maiden.’ Who is a rose? Assembly of Israel”) translator Daniel Matt notes that “shoshanah probably means ‘lily’ or ‘lotus’ in Song of Songs, but here Rabbi Hizkiyah has in mind a rose.” As proof-texts for this translation he cites of number of instances in contemporaneous sources (notably Moses de Leon’s Sefer ha-Rimmon) where shoshanah is read not as “lily” but, almost uniformly, as “rose.” Furthermore, he points out, a 16th century Ladino translation renders the verse “commo la roza…,” etc.

While conceding this point, it does seem as the Zohar is keen on playing with the ambiguity of this word’s meaning. R. Hizkiyah’s reading of the verse continues: “Just as a rose [shoshanah] among thorns is colored red and white, so the Assembly of Israel includes judgement and passion.” The shoshanah’s “red and white” color is read by Matt as a reference to the Rosa gallica versicolor, an old rose variety featuring red and white stripes native to Palestine and introduced to Europe around the time of the Zohar’s composition. (It is also possible that the Zohar is referencing white-colored roses, known to be favored in the aristocratic gardens of this period.)

Keeping this in mind, I’m wary to rule out the possibility that the Zohar may be consciously exploiting—for poetic ends—the capacity of shoshanah to refer both to the (red) rose and the (white) lily, both of which were plants celebrated in romantic verse and rich in theological symbolism. In this sense R. Hizkiyah’s reading is exactly correct: the shoshanah is “colored red and white” in potentia, depending on its interpretation as a rose or a lily.

The shoshanah/rose’s ability to be both red and white is alluded to later in the Zohar in a manner that scholars have connected with the rose’s erotic symbolic association in the middle ages.⁹ Tracking with classical Kabbalah’s general reception as moment of the reemergence of mythic, often carnal language in Jewish literature, the Zohar here aligns this symbol with themes of feminine subjectivity: as the rose was the poetic image favored by the female lover of the Song, so does the rose become a sign of the shekhina in the zoharic imaginary. I copy this passage from the second volume of Zohar below in full (trans. Daniel Matt, as transcribed with accompanying Aramaic in Eitan Fishbane’s The Art of Mystical Narrative):

A frequent rhetorical topos in Zohar—the text shifts from the exegetical “opening” of the master R. Shimon bar Yochai in the first paragraph to a narrative involving two students of the zoharic cohort (R. Abba and R. Yizhaq) in nature. The students characteristic encounter with the natural world “on the way” or “along the road” will, as we will see, serve as a a means of elaborating and illustrating R. Shimon’s hermeneutical gesture. Fishbane describes this poetic strategy gracefully: “the stage-light of the zoharic drama is moved away from the exegetical voice of R. Shimon, but the fictive narration serves the purpose of conveying the hermeneutical point through an alternate means.”¹⁰ We read on:

The rabbis of this narrative are adept, we’re aware, at receiving the natural world as a commentary on Torah. Here, R. Abba’s rose becomes a means of perceiving the secrets of shekhina—divine feminine, divine immanence. Nature is thus read as a site wherein one might overcome nature and perceive the theosophical insights hidden behind its floral signs.

The primacy given to the sense of scent in this verse finds precedent in a bit of midrash from Shir haShirim Rabbah 2:2 (commenting on “like a lily among thorns…”) where it is mentioned, with no shortage of ethnonarcissism, that the world was redeemed by God because of the beauty of Israel—this is compared to a King who decides against destroying an orchard because of the sweet scent of a rose in its midst. Thus: “the world’s existence depends on scent.”¹¹

R. Abba’s here presents the Song’s most famous formula of erotic joy—ani l’dodi v’dodi li, “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine”—and then, strikingly, asks for proof. The evidence he finds for this verse exists in the symbol of the natural object he holds his hand: the rose, in all of its organic functions. Just as the rose petals turns white when distilled in water (rosewater: a therapeutic method known well to the zoharic author/s) so too, as we learn in Isaiah, ones rose-red sins can through repentance turn white as snow—or lilies, for that matter.

R. Abba’s connection of the Song’s formula to the transformative quality of the rose relies on an existing medieval association of the rose with eroticism that finds precedent in the Song itself, where shoshanah is understood to be a sign of the female beloved’s desire. Elliot Wolfson, as always, said it best:

the rose of eros, ever changing from red to white and from white to red, is this very bridge of time that connects being and becoming, a bridge that swerves this way and that way, and thereby facilitates the constant motion that the dance of the erotic dictates.¹²

Strikingly, even given this metamorphic quality, such an association is only possible given the mysterious initial transformation of the word’s meaning (and, thus, the meaning of Song 2:16) from “lily,” in all its virginal whiteness, to the erotic redness of the “rose.”¹³ Rose petals, in a basin of water, can turn white; a lily cannot turn red. We thus have in the history of the Song’s shoshanah a striking instance of a semantic change dictating the development of Jewish theology and exegesis.

Coda: A Marian “shoshanah”

By contrast, we find in the Christian tradition a parallel reading of the Song’s shoshanah which—distinct from that of the kabbalists—maintained its original meaning of “lily.” I have already alluded above to the botanical connection made by Christendom between the shoshanah and Mary in the epithet of the Lilium candidum (“Madonna lily”), a flower subsequently read as symbol of chastity in Catholic iconography. As such, the shoshanah/Lilium candidum has been “rarely absent” as an attribute of Mary in visual representations of the Annunciation and other scenes concerning her virginity.¹⁴

Early Marian litanies, likewise, tend to cite Song 2:2 (“a lily among thorns”) as an epithet of Mary. This verse was not applied exclusively to Mary, however, and was employed just as eagerly to describe Christ himself as well as the Christian community of the early Latin Church.¹⁵ Indeed, the symbol of the lily was used in medieval context as the site of a kind of merging between the bodies of Son and Mother (tracking well with readings of the Song offered by, for instance, Hildegard von Bingen.) We see such a “merging” in a rare motif wherein the sprouting lily-image serves as the very “tree” upon which Christ was crucified—exemplified the Book of Hours illumination above. This symbol of the Virgin’s chastity (a synecdoche of the woman herself) is thus linked poetically to her Son’s death, harmonizing the end of Christ’s life with his conception. Earlier, in this same vein, Beguine hymns relied on imagery borrowed from the Song to communicate the ideal they found in Mary: “I am the honeyed flower perfumed with virtue and grace,” one thirteenth century woman writes, “I am the lily of the valley.”¹⁶

To the extent that one can speak of a tradition of “Marian gardens,” however, lilies don’t make up the whole story. True to the ambiguous meaning of the Song’s shoshanah in the middle ages, Mary was just as often compared to a rose as she was to a lily. Indeed: the dual-meaning of the shoshanah was often evoked in tandem in reference to the mother of God. See the Marian liturgy composed by Fulbert of Chartres (“She emits a fragrance beyond all balms…dewy as a rose, gleaming as the lily”) or even better the hymns of John of Damascus, who insisted that she is “more fragrant than the lily, redder than the rose.”¹⁷

As in the holy Zohar, the shoshanah of Christendom is one that is able to manifest as both white- and red-colored, both sweet-smelling and alluring, chaste and fatal. The floral legacy of the Song of Songs as such is best described in the terms of a dynamic of potency and vivid expression; all that is contained in the budding of the Song blooms vividly in the flowering of exegetical history.

- Compare with the entry for this word in Brown-Driver-Briggs.

- All translations are JPS unless otherwise indicated.

- Munro, Jill M. Spikenard and saffron: the imagery of the Song of Songs. A&C Black, 1995: 81.

- Ibid.

- Fox, Michael V. The Song of Songs and the ancient Egyptian love songs. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985: 9.

- Munro: 82.

- Throop, Priscilla, trans. Hildegard von Bingen’s Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 1998.

- For more on this subject see the exceptional essay: Van Arsdall, Anne, Helmut W. Klug, and Paul Blanz: ‘Mandrake Plant and its Legend.’ In: Old Names — New Growth: Proceedings of the 2nd ASPNS Conference, University of Graz, Austria, 6–10 June 2007, and Related Essays. Eds. Peter Bierbaumer and Helmut W. Klug. Frankfurt/Main: Lang, 2009. 285–346

- As an aside, I learned recently of the symbolic importance assigned to the rose as an anagram of “eros” in Elizabethan occult (namely: Rosicrucian and Masonic) traditions.

- Art of Mystical Narrative, 175.

- See Green, Deborah A. The aroma of righteousness: Scent and seduction in Rabbinic life and literature. Penn State Press, 2011: 124–125.

- Wolfson, Elliot, Michel Conan, and W. J. Kress (eds.). “Rose of Eros and the Duplicity of the Feminine in Zoharic Kabbalah” in Botanical Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovation and Cultural Changes (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2007): 57.

- This half-hearted attempt at color symbolism should (hopefully) not require much explanation.

- Rubin, Miri. Mother of God: a history of the Virgin Mary. Yale University Press, 2009: 344.

- Shuve, Karl. The Song of Songs and the fashioning of identity in early Latin Christianity. Oxford University Press, 2016: 167.

- Rubin, Miri. Mother of God: a history of the Virgin Mary. Yale University Press, 2009: 261.

- Ibid: 139; 73.